For decades, the narrative of American taxation and economic policy has been dominated by the federal government. Debates over income tax brackets, corporate rates, and federal stimulus packages captured the national spotlight. But a quiet, yet profound, revolution is underway, shifting the epicenter of fiscal innovation and conflict from the halls of Congress to state capitols and city halls across the country. This is the State Tax Revolution—a multifaceted struggle where local governments are deploying novel tax strategies to fund essential services, respond to unique economic challenges, and shape their communities’ futures.

Gone are the days of one-size-fits-all federal solutions. In their place, a complex and often contentious patchwork of local fiscal policies has emerged. From the sun-scorched tech hubs of Arizona to the historic towns of New England, states and municipalities are waging their own fiscal wars. These battles are fought over competing visions for society: attracting new businesses versus supporting existing ones, fostering urban density versus preserving suburban character, and addressing historic inequities versus promoting growth-at-all-costs.

This article delves deep into the forces driving this revolution, explores the primary battlefields where these fiscal wars are being fought, and examines the real-world consequences for businesses, residents, and the very fabric of American federalism. It is a story of adaptation, desperation, innovation, and conflict, with the financial health of our communities hanging in the balance.

Part 1: The Battlefields of the Fiscal War

The State Tax Revolution is not a single conflict but a series of interconnected campaigns fought on several distinct fronts. Understanding these battlefields is key to understanding the modern American economic landscape.

1.1 The Corporate Incentive Arms Race

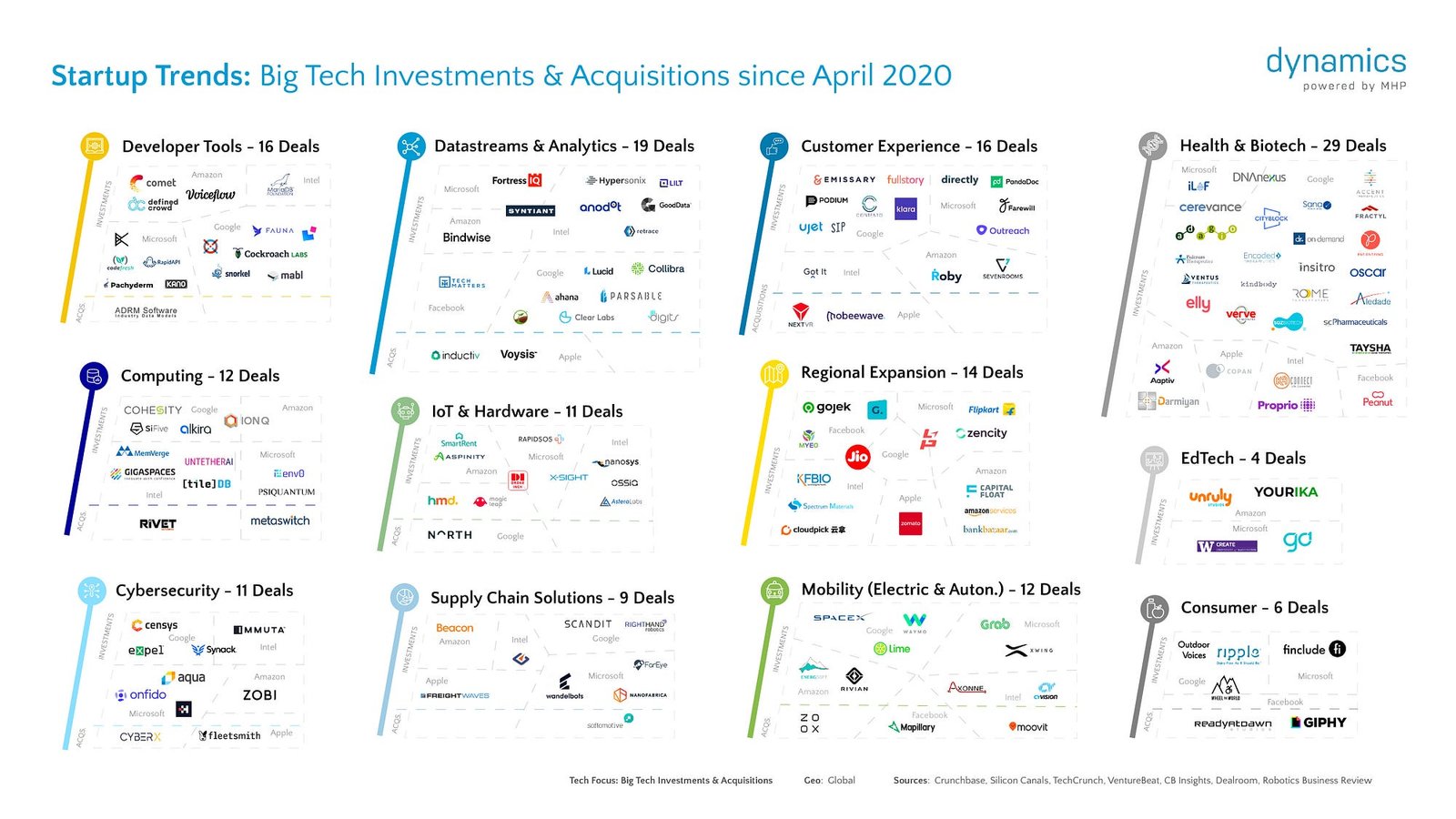

Perhaps the most visible front in this war is the fierce competition among states to attract major corporate investments, particularly from the tech and manufacturing sectors. The prize? Thousands of promised jobs, a boosted local economy, and the prestige of hosting a household name.

The weapons of choice are massive tax incentive packages. States and cities offer a buffet of financial enticements, including:

- Job Creation Tax Credits: Refundable credits for each new job created above a certain wage threshold.

- Property Tax Abatements: Exemptions or steep reductions on property taxes for a set number of years, sometimes decades.

- Investment Tax Credits: Credits based on the amount of capital investment in new facilities or equipment.

- Customized Job Training Grants: State-funded programs to train a workforce specifically for the incoming company.

The most famous recent example is the fierce battle for Amazon’s HQ2 in 2017, which saw 238 cities and regions submit elaborate proposals, offering billions in combined incentives. While the eventual “winners,” Northern Virginia and New York City (which later withdrew due to public backlash), promised over $2 billion in incentives, the process laid bare the extent of this arms race.

Case Study: The Phoenix Metro Area. Arizona has become a magnet for Taiwanese semiconductor giant TSMC and battery manufacturer LG Energy Solution, leveraging its unique geography and aggressive incentive packages. The state offered TSMC a mix of income tax credits, job training funds, and infrastructure improvements worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The goal is to create a new “Silicon Desert,” a strategic bet on the future of advanced manufacturing. Proponents hail the high-paying jobs and supply chain growth. Critics question the high cost per job and whether the public subsidies could be better spent on existing infrastructure and education.

1.2 The Remote Work Reckoning and Residency Laws

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated a trend that has now become a central fiscal challenge: the rise of remote work. For states like New York, California, and Massachusetts, which rely heavily on high-income earners for a disproportionate share of their income tax revenue, the ability of employees to work from anywhere posed an existential threat.

This has sparked a new front: the war over residency and income sourcing. The core conflict is the “convenience of the employer” rule, often dubbed the “telecommuter tax.”

- States with the Rule (e.g., New York, Nebraska, Pennsylvania): These states dictate that if an employee works for a company based within their state but lives and works remotely in another state for their own convenience (not because the employer requires it), the income is still subject to the employer-state’s income tax.

- States without the Rule (e.g., New Hampshire, Florida): These states tax income based on physical presence. They argue that their residents should not be taxed by another state simply because their employer’s headquarters is located there.

This has led to direct legal conflicts. New Hampshire, which has no state income tax, famously sued Massachusetts after the latter state enacted an emergency rule during the pandemic to tax non-residents who were previously commuting to Massachusetts jobs but were now working from home. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately declined to hear the case, leaving the issue unresolved and setting the stage for future interstate battles.

1.3 The “Mansion Tax” and Progressive Localism

At the municipal level, a different kind of war is being waged—one focused on addressing acute local crises like homelessness and affordable housing shortages. Progressive cities, particularly on the West Coast, are pioneering highly localized taxes targeting wealth and high-value real estate transactions.

The most prominent of these is the “mansion tax” or real estate transfer tax. These are tiered taxes imposed on the sale of properties above a certain value, with the rate increasing for higher sale prices. The revenue is often legally earmarked for affordable housing projects and homeless services.

- Los Angeles: Measure ULA: Passed in 2022, this measure imposes a 4% tax on property sales between $5 million and $10 million, and a 5.5% tax on sales of $10 million and more. Despite legal challenges and concerns about dampening the real estate market, it represents a bold attempt to generate substantial revenue from the top of the market to address a city-wide crisis.

- San Francisco and Seattle: Similar transfer taxes have been enacted or proposed in other major cities, reflecting a growing belief that local problems require local, progressive revenue solutions that state and federal governments have failed to provide.

1.4 The Sin Tax Expansion: From Cigarettes to Cannabis and Soda

“Sin taxes” on products like tobacco and alcohol have long been a stable revenue source for states. The modern revolution involves a significant expansion of this concept to new categories, reflecting evolving social norms and public health priorities.

- Cannabis: With the legalization of recreational marijuana in a growing number of states, cannabis taxes have become a major new revenue stream. States typically levy an excise tax on the product at the wholesale level, plus a standard sales tax. Some, like California, also allow local jurisdictions to add their own taxes. This has created a complex regulatory and tax environment, but one that funds everything from substance abuse programs to public schools.

- Sugar-Sweetened Beverages (Soda Taxes): Driven by public health concerns about obesity and diabetes, cities like Philadelphia, Berkeley, and Seattle have implemented taxes on sugary drinks. The aims are dual: to generate revenue for health and education programs and to discourage consumption through higher prices. These taxes are highly controversial, facing fierce opposition from the beverage industry and claims of being regressive, disproportionately affecting lower-income households.

Part 2: The Arsenal: Tools and Tactics of Modern Local Taxation

The strategies outlined above are enabled by a sophisticated and evolving arsenal of fiscal tools.

- Economic Nexus Laws: Following the Supreme Court’s landmark 2018 decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair, states gained the power to require out-of-state online retailers to collect and remit sales tax, even without a physical presence in the state. This has leveled the playing field for local brick-and-mortar stores and created a massive new revenue source for states, fundamentally altering the landscape of e-commerce.

- Tax Increment Financing (TIF): A tool used to finance public infrastructure projects in designated “blighted” areas. The future property tax revenue generated from the increase in assessed value within the TIF district (the “tax increment”) is used to pay for the upfront costs of the development. While powerful for spurring renewal, TIFs are often criticized for diverting future tax revenue from schools and other public services and for sometimes being used in areas that are not genuinely blighted.

- Fees and Special Assessments: As the political difficulty of raising broad-based taxes grows, local governments are increasingly turning to user fees and special assessments. These are charges for specific services, such as trash collection, stormwater management, or sidewalk repairs. Because they are not technically taxes, they can often be implemented with less political fallout, though they too can place a burden on residents.

Part 3: The Fallout: Winners, Losers, and Unintended Consequences

Every war has its casualties, and the State Tax Revolution is no different. The long-term consequences of these localized fiscal battles are still unfolding, but several key trends are emerging.

3.1 The Business Environment: A Labyrinth of Compliance

For businesses, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and those operating in multiple states, the new landscape is a compliance nightmare. Navigating dozens of different sales tax rates, corporate income tax structures, and local business license requirements requires significant resources. A company with remote employees in several states must meticulously track the residency and sourcing rules of each jurisdiction to avoid penalties. This complexity creates a competitive advantage for large corporations with dedicated tax departments, while stifling the growth of smaller businesses.

3.2 The Individual Taxpayer: Trapped in a Web of Residency Rules

For individuals, particularly high-income remote workers, the revolution has created immense complexity and, in some cases, double taxation. The conflict between “convenience rule” states and physical presence states means an employee living in New Hampshire but working remotely for a New York-based company could find themselves filing and paying taxes in both states, then fighting for a credit. This creates uncertainty and can influence major life decisions, such as where to live and for whom to work.

3.3 Exacerbating Inequality

While progressive taxes like the “mansion tax” aim to reduce inequality, other aspects of the revolution may worsen it. The corporate incentive arms race often involves giving massive tax breaks to hugely profitable companies, diverting funds that could be used for public education, infrastructure, and social services that benefit the broader community. This can create a scenario where public resources are used to subsidize private wealth, deepening the divide between the corporate haves and the public-sector have-nots.

Furthermore, regressive taxes like sales taxes and soda taxes place a higher relative burden on low-income families, who spend a larger percentage of their income on taxable goods.

3.4 The Erosion of Fiscal Stability

The move towards hyper-specialized, volatile revenue streams can undermine the long-term fiscal health of states and cities. Revenue from capital gains taxes, cannabis taxes, and transfer taxes can fluctuate wildly with economic cycles. A recession can crater these revenue sources just as the demand for social services increases, creating devastating budget crises. Over-reliance on a single large employer attracted by incentives also poses a risk; if that company fails or relocates, the local economy can collapse.

Read more: AI vs. The Advisor: The Rise of Robo-Investing and What It Means for Your 401(k)

Part 4: The Future of the Fiscal War

The State Tax Revolution shows no signs of abating. Several trends will likely define its next phase.

- The Green Tax Frontier: As climate change accelerates, look for more states and localities to implement carbon taxes, fees on plastic bags and packaging, and incentives for green energy and electric vehicles. These will be framed not just as revenue measures but as essential environmental policy.

- The Digital Asset Dilemma: The rise of cryptocurrency and other digital assets presents a new frontier for taxation. States are already experimenting with how to treat digital assets for sales and income tax purposes, and some are offering tax incentives to attract blockchain businesses, mirroring the corporate arms race of the physical world.

- Interstate Compacts and Federal Intervention: The current system of conflicting state tax laws is unsustainable. There may be a push for more interstate compacts to simplify rules, particularly around remote work taxation and sales tax collection. Alternatively, Congress may feel increasing pressure to step in and create a national framework, as it has previously threatened to do with the “convenience of the employer” rule.

- The Data Economy: As data becomes the world’s most valuable resource, some economists and policymakers are beginning to explore how it could be taxed. Could there be a “data consumption tax” or a tax on the revenue generated from user data by large tech platforms? While still a theoretical frontier, it represents the next logical step in adapting tax systems to a changing economy.

Conclusion

The State Tax Revolution is a definitive feature of 21st-century America. It is a testament to the ingenuity and adaptability of local governments, but also a reflection of a fractured national polity and the retreat of federal leadership on key economic issues. These fiscal wars are reshaping economic geography, influencing individual lives, and redefining the social contract at the local level.

The path forward requires a delicate balance. Local innovation is crucial for addressing unique community needs and experimenting with new policy solutions. However, without greater coordination and a renewed focus on equity and stability, this revolution risks devolving into a chaotic, zero-sum game that leaves businesses bewildered, taxpayers burdened, and the long-term health of our communities in jeopardy. The ultimate challenge for state and local leaders is to wage these fiscal wars not just to win a single corporate headquarters or plug a budget hole, but to build a resilient, fair, and prosperous future for all their citizens.

Read more: Beyond the Piggy Bank: A Parent’s Guide to FinTech Apps Teaching Kids About Money

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What is the main driver behind this “State Tax Revolution”?

The revolution is driven by several converging factors: the devolution of federal policy-making, intense pressure to fund local services (education, infrastructure, public safety), the rise of the remote work economy, stark regional economic disparities, and the desire of local governments to solve hyper-local problems like housing affordability and homelessness that federal policy has failed to address adequately.

Q2: Are these tax incentives for big companies actually worth it for the community?

This is a highly debated question. Proponents argue that the long-term benefits—high-paying jobs, a broader tax base from new residents, and supply chain growth—far outweigh the initial cost. Critics and many economic studies suggest that these deals often fail to deliver the promised number of jobs at the promised quality and divert critical public funds from investments in education and infrastructure that benefit everyone. The cost per job is often astronomically high, and companies sometimes fail to meet their obligations. The value depends heavily on the specific structure of the deal and the presence of “clawback” provisions to recoup funds if promises aren’t met.

Q3: I work remotely for a company in another state. Do I have to pay double taxes?

Not necessarily, but it can be complex. Most states that levy an income tax offer a tax credit for taxes paid to another state on the same income. However, the conflict arises with “convenience of the employer” rules. If you live in a state without this rule but work remotely for a company in a state that has it (like New York), you may have to file and pay taxes in both states. You would then claim a credit in your home state for taxes paid to New York, but you could still end up paying the higher of the two tax rates. It is highly recommended to consult with a tax professional familiar with multi-state residency issues.

Q4: What is the difference between a progressive tax and a regressive tax?

- A progressive tax takes a larger percentage of income from high-income groups than from low-income groups. Examples include federal income tax (with its graduated brackets) and local “mansion taxes.”

- A regressive tax takes a larger percentage of income from low-income groups than from high-income groups. Examples include sales taxes and excise taxes (like on gasoline or cigarettes), because lower-income households spend a higher proportion of their income on taxable goods and services.

Q5: How does the South Dakota v. Wayfair decision affect me as a consumer?

As a consumer, you may now see sales tax applied to online purchases from out-of-state retailers from which you previously bought tax-free. The decision allowed states to require online sellers to collect sales tax based on economic nexus (e.g., a certain amount of sales or transactions in the state), not just physical presence. This has made the online shopping experience more consistent with in-store shopping from a tax perspective and has increased revenue for states.

Q6: With all this complexity, is there a movement to simplify state taxes?

Yes. Organizations like the Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board are working to simplify and standardize sales and use tax collection and administration across states. There is also ongoing discussion about federal legislation to create a national framework for taxing remote workers to resolve the interstate conflicts. However, progress is slow, as states are highly protective of their sovereign taxing authority.

Q7: What can a small business do to manage the complexity of multi-state taxes?

Small businesses should:

- Invest in robust accounting software that can handle multi-state sales tax calculation and filing.

- Consult with a tax advisor or CPA who specializes in state and local tax (SALT) issues.

- Clearly understand “nexus” rules for any state they have economic activity in, including sales, employees, or property.

- Consider using a third-party service that specializes in sales tax compliance for e-commerce businesses.