In the spring of 2021, as the U.S. economy roared back to life from its pandemic-induced slumber, inflation awoke with a vengeance. What was initially dismissed by the Federal Reserve and many economists as “transitory” – a temporary bottleneck of snarled supply chains and pent-up consumer demand – soon revealed itself to be a persistent and deeply embedded problem. By June 2022, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) had skyrocketed to a four-decade high of 9.1%. The Fed, having been caught off-guard, embarked on the most aggressive monetary tightening cycle since the early 1980s, raising its benchmark federal funds rate from near-zero to a 23-year high of 5.25% to 5.5% in a mere 16 months.

The initial phase of the fight was, in a relative sense, successful. By June 2023, CPI had fallen to 3.0%. The descent from the peak was rapid, fueled by the normalization of global supply chains, a shift in consumer spending from goods back to services, and the powerful, immediate impact of the Fed’s rate hikes. It seemed the central bank was on the cusp of a historic victory.

But then, the progress stalled. The final leg of the journey back to the Fed’s steadfast 2% target has proven to be exponentially more difficult. Like a runner who effortlessly covers the first 20 miles of a marathon only to hit “the wall” in the final six, the U.S. economy has entered the most grueling and psychologically taxing phase of the inflation fight. This is “the last mile,” and its stubborn resistance is creating a profound dilemma for the Federal Reserve, testing its resolve, its credibility, and its very strategy for steering the world’s largest economy to a “soft landing.”

This article will dissect the complex anatomy of this stubborn inflation, exploring the powerful structural and cyclical forces making the last mile so arduous. We will examine the Fed’s delicate balancing act, the risks of both over-tightening and premature easing, and what history can teach us about the final stages of defeating a price-wage spiral. The path forward is fraught with uncertainty, and the decisions made in the coming months will have lasting implications for every American household, business, and investor.

Part 1: Anatomy of the “Last Mile” – Why the Final Leg is So Stubborn

The rapid disinflation from 9% to 3% was largely driven by the reversal of temporary, pandemic-era shocks. The current stagnation, with inflation hovering between 3% and 3.7% for over a year, indicates that we are now grappling with more deeply rooted, persistent inflationary pressures. These forces are less sensitive to the Fed’s blunt instrument of interest rate hikes.

1.1 The Shift from Goods to Services Inflation

During the pandemic, inflation was a story of goods: cars, furniture, and appliances saw unprecedented price surges due to supply chain chaos and stimulus-fueled demand. As those supply chains healed and demand normalized, goods inflation collapsed, and in some cases, turned into deflation.

The current inflation story is overwhelmingly about services. The services sector—encompassing everything from healthcare and education to hospitality, housing, and insurance—is far more labor-intensive. This makes its prices intrinsically linked to wage growth. The Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index, clearly shows this divergence: while core goods prices have been flat or falling, core services inflation (excluding energy) remains stubbornly elevated.

- Shelter Inflation: A major component of services inflation is “shelter,” which includes rent and owners’ equivalent rent. While real-time rent measures from private providers like Zillow and Apartment List show a significant cooling, there is a notorious 12-18 month lag before this moderation feeds into the official CPI and PCE data. Shelter inflation, therefore, has been a persistent, albeit slowly fading, tailwind.

- Non-Housing Core Services (a.k.a. “Supercore”): This is the category the Fed is watching most intently. It includes services like healthcare, dining out, haircuts, entertainment, and insurance. Because these services are so dependent on labor, their prices are directly tied to the cost of wages. As long as wage growth remains above the level consistent with 2% inflation (generally estimated at around 3.5% annually), inflation in these sectors will have a hard time falling further.

1.2 A Resilient and Re-balanced Labor Market

The U.S. labor market has defied all expectations of a sharp slowdown. The unemployment rate has remained below 4% for an extended period, a streak not seen in decades. Job growth, while moderating, continues to be robust.

This strength is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it has supported consumer spending and prevented a recession. On the other, it has sustained wage pressures. The quits rate—the number of people voluntarily leaving their jobs—while down from its peak, remains elevated relative to pre-pandemic levels. This indicates workers still feel confident in finding better-paying opportunities, which forces employers to continue raising wages to attract and retain talent.

This has created a “wage-price persistence” feedback loop. Higher wages increase business costs, which are often passed on to consumers as higher prices for services. These higher prices of living then lead workers to demand even higher wages, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that is notoriously difficult to break without a significant slowdown in economic activity.

1.3 The Entrenchment of Inflationary Psychology

Perhaps the most pernicious challenge of the last mile is psychological. After two years of high inflation, businesses and consumers have begun to change their behavior in ways that perpetuate it.

- Business Pricing Power: Companies have grown accustomed to implementing regular, above-average price increases. They have discovered that consumer demand is more resilient than previously thought, allowing them to protect profit margins by passing on higher input costs.

- Consumer Expectations: If consumers expect prices to keep rising significantly, they are more likely to make purchases sooner rather than later, pulling forward demand and adding further inflationary pressure. While long-term inflation expectations have remained relatively “anchored,” short-term expectations can influence immediate economic behavior. The fear is that if high inflation becomes embedded in the public’s mindset, the Fed’s job becomes exponentially harder.

1.4 Structural Shifts in the Global Economy

The “last mile” is also being complicated by a series of structural changes that are inherently inflationary, reversing the disinflationary tailwinds of the past three decades.

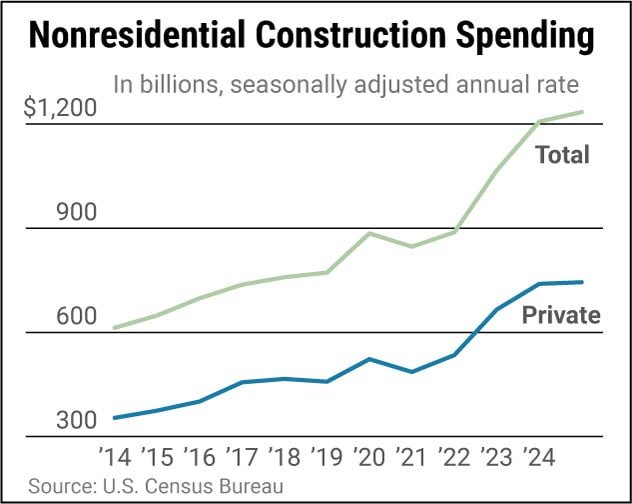

- De-globalization and Re-shoring: The era of hyper-globalization, which kept prices low by outsourcing production to the cheapest possible labor markets, is receding. Geopolitical tensions and supply chain vulnerabilities have prompted a shift towards re-shoring and “friend-shoring” of critical industries. While enhancing economic security, this trend is almost certain to lead to higher production costs.

- Climate Change and Energy Transition: The increasing frequency and severity of climate-related disasters disrupt agricultural and industrial production, causing price spikes. Furthermore, the transition to a green economy, while vital, requires massive investment in new technologies and infrastructure, which can be inflationary in the near-to-medium term.

- Demographic Pressures: Aging populations in the U.S. and other developed nations are shrinking the pool of available workers, contributing to structural labor shortages and putting persistent upward pressure on wages.

Part 2: The Fed’s Unenviable Dilemma – A High-Wire Act Over Uncharted Territory

Faced with this stubborn “last mile” inflation, the Federal Reserve finds itself in a policy quandary of immense complexity. Its dual mandate—to achieve maximum employment and stable prices—is being stretched to its limits.

2.1 The Risk of Premature Declaring Victory

The greatest fear among inflation hawks is that the Fed, under political and market pressure, will prematurely pivot to interest rate cuts before inflation is definitively vanquished. History offers a stark warning. In the 1970s, the Fed repeatedly tightened policy to curb inflation, only to reverse course and cut rates at the first sign of economic weakness. Each time, inflation roared back even stronger, requiring even more painful medicine—the Volcker shock of the early 1980s—to finally break its back.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell and other officials have repeatedly stated they are determined not to repeat that mistake. They have communicated a “higher-for-longer” stance, insisting they need to see several more months of encouraging inflation data before considering rate cuts. The risk of cutting too soon is that it could re-ignite demand, un-anchor inflation expectations, and ultimately force the Fed to restart its tightening cycle, causing even greater economic damage.

2.2 The Risk of Overtightening and Triggering a Recession

On the other side of the dilemma lies the risk of the Fed keeping policy too restrictive for too long. The full effects of monetary policy operate with “long and variable lags,” estimated to be 12 to 18 months. This means the economy is still absorbing the impact of the rate hikes implemented throughout 2022 and 2023.

There are already clear cracks in the foundation:

- Strained Consumer Finances: Lower-income households have largely exhausted the excess savings accumulated during the pandemic. Credit card debt is at a record high, and delinquency rates are rising.

- Cooling Housing Market: Mortgage rates hovering near 7% have crushed affordability, freezing the existing home sales market and slowing new construction.

- Tighter Lending Standards: The regional banking turmoil of early 2023 made financial institutions more cautious, leading to a significant tightening of credit conditions for both businesses and consumers, which acts as a drag on economic growth.

If the Fed continues to hold rates at their current restrictive level while the economy is naturally slowing, it could tip the balance from a slowdown into a full-blown, unnecessary recession, costing millions of jobs.

2.3 The “Soft Landing” Mirage?

The Fed’s stated goal is a “soft landing”—a scenario where inflation returns to 2% without a significant rise in unemployment. This feat has been described as rare and difficult, akin to threading a needle. The current resilience of the labor market offers hope, but the stubbornness of services inflation suggests the path is narrowing.

The central bank may be facing a choice it desperately wants to avoid: accept a period of slightly higher inflation (e.g., 2.5% to 3%) to preserve employment, or deliberately engineer an economic downturn to forcibly crush the remaining inflationary pressures. The latter option would shatter the dream of a soft landing.

Part 3: Historical Precedents and the Lessons for Today

The current “last mile” problem is not entirely without historical precedent. Examining past inflation battles provides crucial, albeit imperfect, lessons.

3.1 The Ghost of the 1970s

As mentioned, the 1970s serve as the primary cautionary tale against premature easing. The Fed’s stop-and-go policies during that decade allowed inflation to become entrenched, demonstrating that once the public loses faith in the central bank’s resolve, the cost of restoring price stability becomes immensely painful.

3.2 The “Soft Landing” of the Mid-1990s

A more optimistic parallel can be drawn to the mid-1990s. Then-Fed Chair Alan Greenspan, facing rising inflation fears, engineered a series of pre-emptive rate hikes in 1994-1995. After doubling the federal funds rate from 3% to 6%, the Fed successfully slowed the economy without causing a recession, allowing for a period of sustained growth and low inflation. The key to this success was a belief that productivity was rising, which allowed the economy to grow faster without generating inflation—a dynamic that some economists argue could be repeating today with the AI and automation boom.

3.3 The Global Disinflationary Era (1990s-2019)

The three decades preceding the pandemic were defined by powerful disinflationary forces: globalization, technological innovation, and favorable demographics. This period created a “low-flation” mindset within central banks, which now find their policy toolkit and institutional mindset tested by a fundamentally different economic paradigm.

Read more: Will the Fed Cut Interest Rates Again This Year?

Part 4: The Path Forward – Scenarios for the Endgame

As of late 2024, the Fed is in a holding pattern, carefully monitoring the data. The path to 2% inflation is unlikely to be a smooth, linear descent. Several scenarios are possible.

- The “Soft Landing” Scenario (The Base Case): Inflation resumes a gradual, if bumpy, decline towards 2% over the course of 2025. The labor market cools modestly, with wage growth slowing to a pace consistent with 2% inflation, but without a sharp spike in unemployment. The Fed begins a slow, cautious cutting cycle, managing to normalize policy without derailing the expansion.

- The “No Landing” / Stagflation-Lite Scenario (A Growing Concern): The economy continues to grow at a steady pace, and the labor market remains tight, preventing inflation from falling back to 2%. This forces the Fed to maintain restrictive rates for much longer than markets expect, leading to a prolonged period of “financial repression” where growth is mediocre but inflation remains stubbornly above target.

- The “Hard Landing” Scenario (The Tail Risk): The lagged effects of the Fed’s rate hikes finally hit the economy with full force. Consumer spending buckles, business investment freezes, and unemployment rises sharply. The Fed is forced into rapid, emergency rate cuts to stave off a deep recession, but the victory over inflation comes at a high social and economic cost.

Conclusion: A Test of Resolve and Patience

The “last mile” of the inflation fight is indeed the hardest because it pits the powerful, immediate tools of monetary policy against the deep-seated, structural realities of the modern economy. The easy wins from fixing supply chains are behind us. What remains is a battle against wage-price dynamics, inflationary psychology, and a fundamentally changed global landscape.

The Federal Reserve’s resolve is being tested like never before in the 21st century. It must navigate by a data-dependent compass through a fog of conflicting signals—a strong labor market versus sticky inflation, resilient consumers versus growing financial strains. Its success or failure will hinge on its patience and its willingness to resist the siren calls of political pressure and market euphoria.

For businesses, investors, and households, this implies a prolonged period of uncertainty and higher-than-accustomed interest rates. The era of “free money” is over. The new economic reality demands resilience, flexibility, and a preparedness for a future where the cost of capital is higher, and the path to price stability is a marathon, not a sprint. The final mile will determine not just the fate of this economic cycle, but the credibility of the central bank for years to come.

Read more: How Does the Federal Reserve Impact Everyday American Borrowers?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What exactly is meant by the “last mile” of inflation?

A: The “last mile” refers to the final and most difficult stage of returning inflation to the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. The initial drop from a peak (like 9.1%) to around 3% is often faster, driven by fixing temporary issues like broken supply chains. The last leg, from 3% down to 2%, is harder because it involves battling more persistent, underlying pressures like wage growth in the services sector and entrenched inflation expectations.

Q2: Why can’t the Fed just cut interest rates now to help the economy?

A: The Fed’s primary mandate is price stability. Cutting interest rates prematurely, before inflation is definitively under control, could re-stimulate demand and cause inflation to surge back. This would undo all the progress made and could force the Fed to raise rates even more aggressively later, potentially causing a severe recession. Their current “higher-for-longer” stance is a deliberate strategy to avoid this mistake.

Q3: Is the official inflation data (like CPI) accurate? Doesn’t it feel like inflation is still much higher?

A: The official CPI is a broad measure based on a basket of goods and services. It is accurate for the average across the entire economy. However, individual experiences can vary significantly. For example, if you are in the market for a car, rent, or insurance, you are facing price increases far above the 3% headline rate. Furthermore, while the rate of price increase has slowed, the price level itself remains high. People feel this acutely, as their budgets are still stretched by the cumulative price hikes of the last three years.

Q4: What is the difference between a “soft landing” and a recession?

A: A soft landing occurs when the Fed successfully cools the economy and brings down inflation without causing a significant rise in unemployment or a major economic contraction. It’s a gentle slowdown. A recession is a significant decline in economic activity that lasts for more than a few months, typically marked by a sharp rise in unemployment, falling retail sales, and negative GDP growth. A “hard landing” is when the Fed’s actions directly cause a recession.

Q5: How do wage increases contribute to inflation?

A: In a services-dominated economy, labor is a major cost for businesses. When wages rise consistently faster than productivity, businesses often pass those higher labor costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices for services like healthcare, dining, and personal care. This can create a feedback loop, known as a wage-price spiral, where higher prices lead workers to demand even higher wages, which in turn leads to further price increases.

Q6: What can I do to protect my finances in this high-inflation, high-interest-rate environment?

A:

- Budgeting: Scrutinize your spending, focusing on needs versus wants.

- High-Yield Savings: Park emergency funds in high-yield savings accounts or money market funds to earn a return that outpaces inflation.

- Debt Management: Prioritize paying down high-interest debt, especially credit cards, as borrowing costs are now much higher.

- Investing: Maintain a long-term, diversified investment strategy. While markets are volatile, history shows they tend to outperform inflation over time.

- Salary Negotiation: In a tight labor market, be prepared to make a case for a raise that at least keeps pace with inflation to protect your purchasing power.

Q7: Are we headed for another period of 1970s-style “stagflation”?

A: Most economists believe a return to full-blown 1970s stagflation (a combination of high inflation and high unemployment) is unlikely. The current unemployment rate remains very low, which is the opposite of “stagnation.” However, a risk of “stagflation-lite” exists—a scenario where growth is weak and unemployment rises modestly while inflation remains stubbornly above 2%. The Fed’s entire policy is designed to prevent this outcome.

Q8: When does the Fed actually decide to cut interest rates? What are they watching?

A: The Fed is data-dependent. They are closely monitoring three key areas:

- Inflation Data: They need to see a sustained, sequential decline in core inflation measures, especially in services, moving convincingly toward 2%.

- Labor Market Data: They are looking for clear signs of cooling, such as a lower number of job openings (the JOLTS report) and a moderation in wage growth.

- Growth and Consumer Data: They are watching for signs that the economy is slowing to a sustainable pace without collapsing.