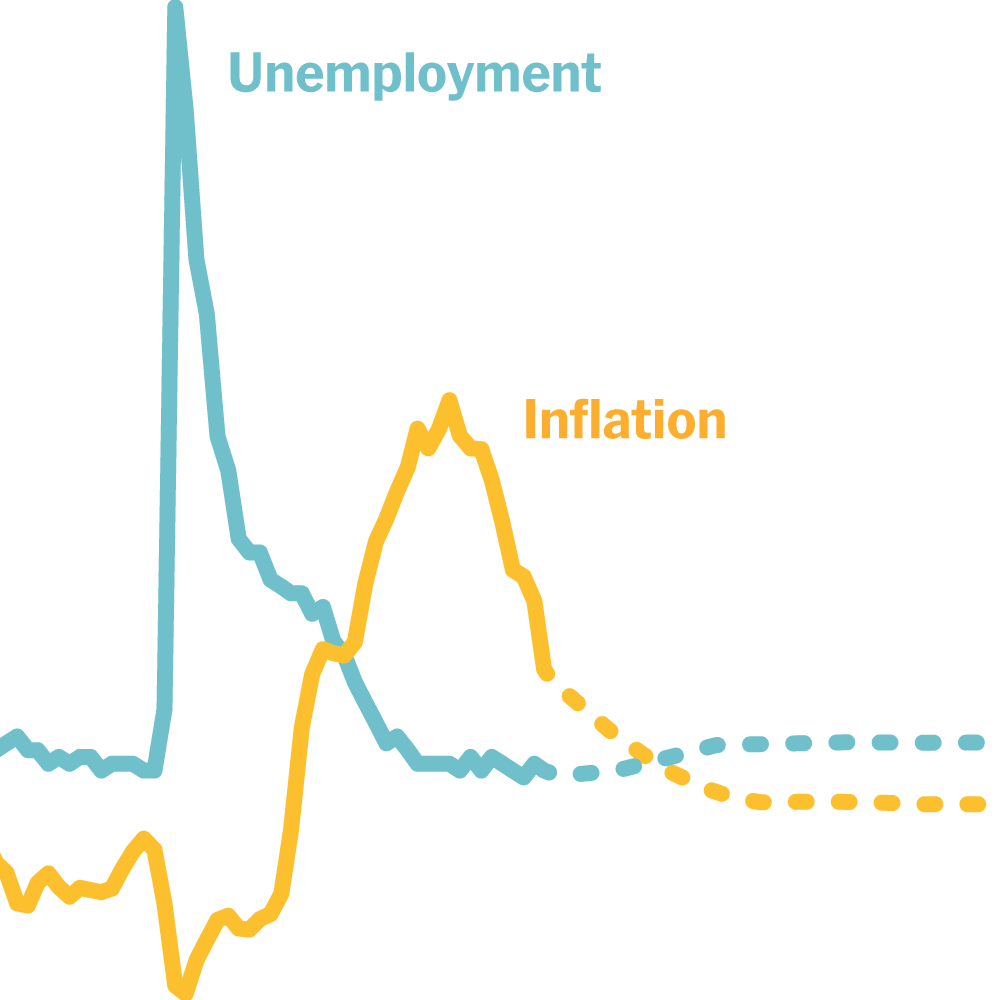

The United States economy is in the midst of one of the most closely watched and delicate macroeconomic experiments in modern history. After inflation surged to a 40-year high in 2022, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) embarked on the most aggressive interest rate hiking cycle since the 1980s. Conventional economic wisdom dictated that such forceful action would inevitably plunge the economy into a recession—the proverbial “hard landing.” Yet, against all odds, the economy has proven remarkably resilient. As we move through 2024, the central question for investors, policymakers, and everyday Americans is no longer about averting a downturn, but about achieving the elusive “soft landing”: a scenario where inflation is subdued back to the Fed’s 2% target without triggering a significant spike in unemployment or a deep recession. This article delves into the intricate mechanics of this high-stakes endeavor, analyzing the current economic data, the forces driving resilience, the persistent risks, and the probable path ahead.

Introduction: The Anatomy of a Policy Dilemma

A “soft landing” is the holy grail of central banking. It is a rare and delicate outcome, akin to a pilot navigating a giant aircraft through turbulent storms and descending smoothly onto the runway without a jolt. The historical record is sparse; the Fed’s success in 1994-95 under Alan Greenspan is often cited as the prime example, though the economic context was vastly different.

The current cycle is unique in its origins. The inflation of 2021-2022 was not driven by an overheated economy alone but by a “perfect storm” of factors: unprecedented fiscal stimulus during the pandemic, supply chain meltdowns, a surge in consumer demand for goods, and later, the energy and food price shocks following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Fed, initially labeling the inflation “transitory,” was forced to play catch-up, raising the benchmark federal funds rate from near-zero in March 2022 to a 23-year high of 5.25% to 5.50% by July 2023.

The textbook outcome of such rapid tightening is a recession. Higher borrowing costs are meant to cool the economy by making mortgages, car loans, and business investment more expensive, thereby reducing demand and easing price pressures. The fact that this has not yet happened—and that the economy continues to add jobs and grow—is what makes the current moment so fascinating and fraught with uncertainty. This analysis will dissect whether this resilience is sustainable or merely the calm before the storm.

Section 1: The Case for the Soft Landing – Reasons for Optimism

A confluence of powerful, and in some cases, novel, economic forces has bolstered the case for a soft landing in early 2024.

1.1. Disinflationary Progress is Undeniable

The most compelling evidence for the soft landing narrative is the significant progress already made on inflation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI), which peaked at 9.1% year-over-year in June 2022, has fallen dramatically. As of the latest data, it stands in the 3.1-3.4% range. The Fed’s preferred gauge, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index, has shown similar improvement, falling from a peak of 7.1% to around 2.6% for the headline number. The core PCE (excluding food and energy), which the Fed watches more closely as an indicator of underlying inflation, has also declined from 5.6% to 2.8%.

This disinflation has been driven by:

- The Unwinding of Supply Chains: The resolution of shipping logjams, normalized semiconductor production, and replenished inventories have reversed the goods-based inflation that dominated the early phase.

- The Rebalancing of the Labor Market: While still strong, the labor market has cooled from its frenzied peak. Job openings have declined from a record 12 million to levels around 8.8 million, and wage growth, as measured by the Employment Cost Index, has moderated, reducing fears of a 1970s-style wage-price spiral.

1.2. Remarkable Labor Market Resilience

A soft landing is defined by the preservation of the labor market. So far, the data has been astonishingly positive. The unemployment rate has remained below 4% for an extended period, a streak not seen since the 1960s. Job creation continues to be robust, consistently beating forecasts. This strength has provided American households with sustained income, allowing consumer spending—the primary engine of the U.S. economy—to remain healthy.

1.3. The “Immune System” of the Corporate and Household Sectors

The period of near-zero rates during the pandemic had an unintended consequence: it fortified the balance sheets of both corporations and households.

- Corporate Fortitude: Many companies took advantage of low rates to issue long-term, fixed-rate debt. This has insulated them from the immediate shock of higher rates. Profit margins, while moderating, have generally held up, allowing businesses to avoid mass layoffs for now.

- Household Financial Health: Similarly, many homeowners locked in 30-year mortgages at rates below 3%, making them immune to the direct impact of the Fed’s hikes on their housing costs. Excess savings accumulated during the pandemic, while being drawn down, have provided a buffer for many families. Delinquency rates on consumer loans, while rising from historic lows, remain relatively contained.

1.4. Positive Productivity Surge

A key, and often overlooked, factor in the soft landing thesis is the recent surge in productivity. Nonfarm productivity rose at a 3.2% annual rate in the fourth quarter of 2023. When workers produce more per hour, it allows the economy to grow faster without generating inflation. It also helps companies absorb higher wage costs without needing to raise prices, effectively paying for wage increases through efficiency gains. This is a powerful disinflationary force that strengthens the case for a soft landing.

Section 2: The Case for the Hard Landing – Lingering Risks and Headwinds

Despite the optimistic data, significant risks remain. The full impact of monetary policy operates with “long and variable lags,” and it is possible that the cumulative effect of 11 rate hikes has yet to be fully felt by the economy.

2.1. The Stubborn “Last Mile” of Inflation

While inflation has fallen dramatically, the final push from 3% to the Fed’s 2% target may be the most difficult. The easy wins from healing supply chains are in the past. The remaining inflation is increasingly concentrated in services—sectors like healthcare, insurance, education, and hospitality. These prices are notoriously “sticky” because they are more directly tied to domestic wage growth. With the labor market still tight, services inflation may prove persistent, requiring a more significant economic slowdown to tame.

2.2. The Restrictive Reality of Monetary Policy

It is critical to assess the stance of policy not by how high rates are, but by how they compare to the neutral rate of interest (often denoted as r*). The neutral rate is the theoretical level that neither stimulates nor restrains the economy. While it is unobservable, most estimates suggest the current federal funds rate of 5.25-5.50% is significantly above neutral, meaning policy is actively restrictive. The longer policy remains this restrictive, the greater the risk of “breaking” something in the financial system or triggering a sharp downturn. History is littered with examples of the Fed overtightening.

2.3. Geopolitical Wild Cards

The global landscape remains a source of significant inflationary risk.

- Conflict in the Middle East: The war in Gaza and ongoing attacks on shipping in the Red Sea have disrupted global trade routes, potentially leading to renewed delays and increased shipping costs.

- The War in Ukraine: Continued conflict threatens global supplies of grain and other commodities.

- OPEC+ Dynamics: Any decision by the oil cartel to constrain supply could send energy prices soaring, reigniting a key component of headline inflation.

These supply-side shocks are outside the Fed’s control and could complicate the inflation fight, potentially forcing the Fed to keep rates higher for longer than the domestic economy can bear.

2.4. Cracks in the Foundation: Commercial Real Estate and Regional Banks

The commercial real estate (CRE) sector, particularly office space, is under severe stress due to the rise of hybrid work, high vacancy rates, and the burden of maturing debt that must be refinanced at much higher rates. This poses a direct threat to the regional banks that hold a large proportion of CRE loans. A wave of defaults could trigger a credit crunch, making it harder for small and medium-sized businesses—the primary drivers of U.S. employment—to access capital. This was previewed by the banking mini-crisis of March 2023 (Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank) and remains a potent vulnerability.

2.5. The Exhaustion of Consumer Resilience

The “excess savings” buffer is not infinite. Estimates vary, but research from the San Francisco Fed suggests that these excess savings have been largely depleted for the population as a whole. Meanwhile, consumer debt (credit cards, auto loans) has hit record highs, and delinquencies are ticking up. If the labor market weakens significantly, the primary support for the economy—consumer spending—could falter abruptly.

Read more: The Green Subsidy Arms Race: How the IRA Is Reshaping American Industry and Global Competition

Section 3: The Fed’s Playbook and The Path Forward

The Federal Reserve, under Chairman Jerome Powell, has been meticulously navigating this minefield. Its current strategy can be characterized as “higher for longer,” with a strong emphasis on data-dependency.

3.1. The Shift from Hiking to Holding

Having likely reached the peak of the rate cycle, the Fed’s primary tool is now patience. They are holding rates at a restrictive level to ensure that inflation is sustainably moving toward 2%. They have explicitly pushed back against market expectations of rapid, early rate cuts, fearing that premature easing could undo their hard-won progress by re-igniting demand and inflation expectations.

3.2. The Data-Dependent Framework

Every Fed statement and speech now emphasizes that future policy moves will be guided by the incoming data. The key metrics they are watching are:

- Monthly CPI and PCE reports: For confirmation that disinflation is continuing, especially in core services.

- The Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS): As a gauge of labor market tightness.

- The Employment Report: Specifically, wage growth and the unemployment rate.

- Consumer and Business Sentiment Surveys.

3.3. The Balance of Risks

The Fed’s calculus is a delicate balance between two primary risks:

- The Risk of Overtightening: Keeping policy too restrictive for too long, causing an unnecessary recession and job losses.

- The Risk of Undertightening: Cutting rates too soon, allowing inflation to become re-entrenched, which would require an even more painful policy response later.

As of early 2024, the Fed appears to view these risks as nearly balanced, but with a slight tilt towards guarding against the second risk—letting inflation stay high.

Conclusion: The Verdict on the Soft Landing

The U.S. economy has defied the pessimists for over a year. The path to a soft landing is now visible and, for the first time, appears to be the most likely scenario. The combination of significant disinflation without a material rise in unemployment is a monumental achievement.

However, declaring victory would be premature. The “last mile” of inflation will be a tough slog, the lagged effects of policy are still circulating through the economy, and external geopolitical shocks remain a constant threat. The most probable outcome is a “soft-ish” landing: a scenario where the economy avoids a traditional, deep recession but experiences a period of below-trend growth and a modest rise in the unemployment rate to around 4.5%. This would be enough to finally quell the remaining inflationary pressures and allow the Fed to begin a gradual cutting cycle in the second half of 2024.

The Fed is walking a tightrope, but it has already navigated the most dangerous part of the crossing. The final steps require a steady nerve, a focus on the data, and perhaps, a little bit of luck. For now, the American economy continues its improbable and historic balancing act.

Read more: The Looming Showdown: Can Social Security and Medicare Survive the Coming Demographic Cliff?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What exactly is a “soft landing” in economic terms?

A: A soft landing refers to the desired outcome of a central bank’s monetary tightening cycle, where it successfully slows the economy enough to bring high inflation down to its target (2% for the Fed) without causing a significant economic contraction or a sharp rise in unemployment. It’s a delicate balancing act between cooling demand and avoiding a recession.

Q2: Why is the “last mile” of inflation considered the hardest?

A: The initial drop in inflation was aided by one-off factors like the resolution of supply chain bottlenecks and falling energy prices. The remaining inflation is now concentrated in service sectors (e.g., healthcare, rents, dining out), which are more directly tied to domestic wage growth. Since wages tend to be “sticky” and slow to decline, squeezing out this last bit of inflation may require a more pronounced softening of the labor market.

Q3: How do high interest rates actually slow down the economy and fight inflation?

A: Higher interest rates make borrowing more expensive for everyone. This discourages consumers from taking out mortgages and car loans, dissuades businesses from investing in new equipment or expansion, and strengthens the currency, making exports more expensive. All of these actions reduce overall demand in the economy. When demand cools, sellers lose their pricing power, and inflation pressures diminish.

Q4: The economy seems strong, so why is the Fed even considering cutting rates?

A: The Fed’s mandate is to promote maximum employment and stable prices (2% inflation). Once they are confident that inflation is sustainably moving toward 2%, their goal shifts from restricting the economy to simply neutralizing policy to avoid an unnecessary downturn. Holding rates too high for too long after inflation is controlled could needlessly choke off growth and jobs. Rate cuts are a pre-emptive measure to guide the economy to a sustainable pace of growth.

Q5: What are the biggest threats to the soft landing right now?

A: The primary threats are:

- Persistent Services Inflation: If wage-driven services inflation doesn’t cool.

- Geopolitical Shocks: A major spike in oil prices due to global conflict.

- A Credit Crunch: Trouble in the commercial real estate sector spilling over to regional banks and restricting lending.

- Policy Error: The Fed misjudging the situation by either cutting rates too late (causing a recession) or too early (re-igniting inflation).

Q6: How does a strong U.S. job market make the Fed’s job harder?

A: A very strong labor market, with low unemployment and rapid wage growth, can sustain high levels of consumer demand. This demand gives companies the ability to continue raising prices, fueling inflation. If the labor market doesn’t cool at least moderately, it could be very difficult for the Fed to bring services inflation down to its 2% target.