If you were to glance at the financial headlines in the closing months of 2023 and into 2024, you might see a story of remarkable resilience. The S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite were reaching record highs, corporate profits were robust, and the feared recession had, thus far, been skillfully avoided. From the vantage point of Wall Street, the economic picture appeared to be strengthening, a testament to the enduring power of American capitalism.

But take a walk down Main Street—the figurative home of small businesses, working families, and everyday consumers—and you would likely hear a different story. At the grocery store, the gas pump, and the family budget meeting, the dominant sentiment is one of strain, frustration, and a pervasive feeling that the economy is not working for the average person. Despite strong wage growth on paper, the constant climb in the cost of living means many feel they are falling behind.

This chasm between Wall Street’s exuberance and Main Street’s anxiety is more than just a perception gap; it is a fundamental feature of the modern post-pandemic economy. It is a divide driven by different metrics, different timelines, and vastly different lived experiences. To understand the true health of the nation, we must decode this sentiment divide, exploring the structural, psychological, and political forces that allow a booming stock market to coexist with a beleaguered consumer psyche.

This article will dissect the key drivers of this divergence, analyze the data behind both narratives, and explore whether this chasm can be bridged or if it represents a new, permanent tension in the American economic landscape.

Section 1: Defining the Divide – What We Mean by Main Street and Wall Street

Before delving into the causes, it’s crucial to define our terms, as “Main Street” and “Wall Street” are both literal places and powerful cultural symbols.

Main Street embodies the real economy—the world of:

- Households and Consumers: Their primary concerns are employment, wages, and the cost of living (housing, food, healthcare, transportation, education).

- Small Businesses: The engines of local job creation, focused on cash flow, local demand, and navigating regulatory and competitive challenges.

- Local Communities: The economic health of towns and cities, measured by storefront vacancies, public services, and community well-being.

For Main Street, success is measured in purchasing power—the ability to afford a good quality of life, save for the future, and withstand financial shocks. Their economic data points are the price of milk, the monthly mortgage payment, and the balance in their checking account.

Wall Street represents the capital markets—the ecosystem of:

- Large Corporations (Publicly Traded): Their mandate is to maximize shareholder value, primarily through profit growth and increasing stock prices.

- Institutional Investors: Pension funds, hedge funds, and asset managers who deploy vast sums of capital in pursuit of returns.

- Financial Intermediaries: Investment banks, brokerages, and exchanges that facilitate the flow of capital.

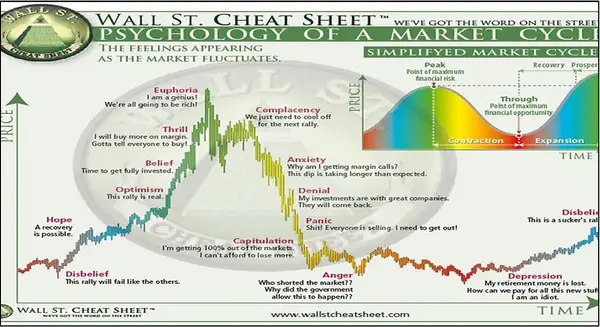

For Wall Street, success is measured by metrics like the S&P 500, corporate earnings per share (EPS), price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, and GDP growth. It is a forward-looking, expectations-driven world where sentiment is often as important as immediate reality.

The fundamental disconnect arises because these two worlds, while interconnected, operate on different principles and are impacted by economic forces in different ways and at different times.

Section 2: The Pillars of the Divide – Why the Disconnect Exists

The current sentiment gap is not an anomaly; it is the result of several powerful, interconnected forces that have been amplified by the unique circumstances of the post-2020 era.

Pillar 1: The Inflationary Squeeze vs. Corporate Pricing Power

This is the most visceral and daily felt aspect of the divide.

- The Main Street Experience: For consumers, inflation is not a abstract percentage; it’s a tangible erosion of their standard of living. The surge in prices for essentials—food, energy, shelter, and services—has far outstripped average wage gains for much of the post-pandemic period. While nominal wages have risen significantly, real wages (wages adjusted for inflation) have been a battleground. Even as real wage growth turned positive in 2023, it has not been enough to fully offset the cumulative price increases of the previous two years. The psychological scar of seeing a $100 grocery trip buy significantly less than it did in 2019 is profound and long-lasting.

- The Wall Street Rationale: For large corporations, the high-inflation environment presented an opportunity. Many companies with strong market power exercised significant pricing power. They were able to pass increased input costs onto consumers and, in many cases, raise prices beyond their own cost increases, leading to record or near-record profit margins. Sectors like energy, consumer staples, and automotive saw enormous profitability. For investors, this translated directly into higher earnings per share and strong stock performance. What was a squeeze on Main Street became a tailwind for Wall Street.

Pillar 2: The Interest Rate Dichotomy

The Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate hiking campaign, designed to combat inflation, created a classic “two-edged sword” with wildly different impacts.

- The Main Street Burden: Higher interest rates directly increase the cost of borrowing for the things that define middle-class life and small business operation.

- Mortgages: The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate more than doubled from its lows, pushing homeownership out of reach for many and freezing the housing market, as existing homeowners with sub-3% rates are reluctant to sell.

- Auto Loans & Credit Cards: Financing a car became significantly more expensive, and credit card APRs soared, punishing those who carry a balance.

- Small Business Loans: The cost of capital for expansion, inventory, and payroll increased, stifling investment.

- The Wall Street Benefit (Initially): For Wall Street, higher interest rates were a mixed bag but initially a sign of strength. The Fed was hiking because the economy was robust. Higher rates also provided a more attractive, low-risk return through bonds and savings accounts, drawing money away from equities. However, a “higher for longer” narrative eventually creates headwinds for stock valuations, as future corporate earnings are discounted at a higher rate. Yet, a resilient economy and strong corporate profits have allowed markets to look past this, for now.

Pillar 3: The K-Shaped Recovery and Wealth Inequality

The pandemic recession was unique, giving rise to a “K-shaped” recovery where different parts of the economy recovered at starkly different paces.

- The Downward Leg of the K (Main Street): Lower-wage service workers, those in industries decimated by lockdowns, and individuals without assets bore the brunt of the initial economic shock. While the recovery was swift due to unprecedented fiscal stimulus, the inflationary aftermath has hit this group the hardest, as they spend a larger proportion of their income on essentials.

- The Upward Leg of the K (Wall Street): Knowledge workers, who could work remotely, saw their lives and finances largely uninterrupted. More importantly, the asset-owning class—the roughly 50-60% of Americans who own stocks, predominantly through retirement accounts—benefited enormously from the initial stimulus-fueled market rally. However, stock ownership is highly concentrated. The top 10% of households own about 89% of all stocks, meaning the gains from a rising market are disproportionately enjoyed by the wealthy.

This K-shaped dynamic has exacerbated pre-existing wealth inequality. The Main Street experience is shaped by paycheck-to-paycheck pressures, while the Wall Street narrative is driven by the portfolio gains of the affluent.

Pillar 4: The Lag of Economic Data vs. Lived Experience

Economic data is inherently backward-looking and subject to revision, while consumer sentiment is a real-time, forward-looking feeling.

- The Official Narrative: Government reports on inflation (CPI) show it cooling significantly from its 9.1% peak. The unemployment rate has remained at historically low levels, below 4%, a figure that traditionally signals a very strong economy. GDP growth has surprised to the upside. By these standard metrics, the economy is in excellent shape—the much-touted “soft landing.”

- The Lived Reality: For consumers, “cooling inflation” does not mean prices are falling (deflation); it means they are rising more slowly. The price level is still painfully high. A 3% inflation rate on top of the 40-year high is still a painful increase. Furthermore, the “vibecession” concept—a recession in feeling rather than in hard data—has taken hold. The constant negative news cycle, the memory of recent economic pain, and the slow, sticky nature of service-sector inflation (like haircuts, restaurant meals, and repairs) make the official data feel disconnected from daily life.

Section 3: The Psychological and Media Amplifier

The divide is not just economic; it is psychological and amplified by modern media.

- Recency Bias and Anchoring: Consumers are psychologically “anchored” to pre-pandemic price levels. The shock of the rapid price increases from 2021-2023 has created a powerful negative baseline against which all current data is judged.

- Political Polarization: Economic sentiment has become increasingly correlated with political affiliation. Supporters of the party out of power are far more likely to express negative views on the economy, regardless of the underlying data, deepening the perception of a divide.

- Media Narratives: Financial media focuses on stock indices and corporate earnings. Local and social media are flooded with stories of high grocery bills and housing unaffordability. These parallel information streams create two self-reinforcing, and often opposing, realities.

Section 4: Case Studies in the Divide

1. The Grocery Aisle:

A large packaged food company reports stellar quarterly earnings, beating analyst estimates, and its stock price jumps. They achieved this by implementing strategic price increases and “shrinkflation” (reducing product size while holding price constant). On Main Street, the same consumer who is frustrated by the smaller box of cereal or the more expensive jar of pasta sauce is, through their 401(k), indirectly a part-owner of that company. Their role as a consumer and as an investor are in direct conflict.

2. The Labor Market Conundrum:

Wall Street cheers a strong jobs report, seeing it as evidence of a resilient economy. However, that same report, showing strong wage growth, can spook markets because it might lead the Fed to keep interest rates higher for longer to prevent wage-price spirals. Meanwhile, on Main Street, workers see their paychecks grow but feel no better off because their expenses are growing just as fast, if not faster.

Read more: The Trillion-Dollar Defense: A Look Inside the U.S. Military Budget and National Security Spending

Section 5: Bridging the Chasm? Potential Pathways to Convergence

Can these two worlds ever realign? Several scenarios could bridge the sentiment divide:

- Sustained Real Wage Growth: The most direct path. If inflation remains subdued and wage growth continues to outpace price increases for a sustained period—12 to 18 months—the cumulative effect could begin to repair household balance sheets and improve consumer sentiment materially.

- A Meaningful Cool-Down in Housing Costs: Shelter is the largest component of the CPI and a major household expense. A significant moderation in rent growth and a decline in mortgage rates would provide immense relief to Main Street and could alter the economic mood dramatically.

- A Market Correction: A significant downturn in the stock market would bring Wall Street’s mood more in line with the prevailing anxiety on Main Street. While painful for investors, it would eliminate the cognitive dissonance of a “booming” market alongside a “struggling” public.

- The Passage of Time: As the shock of the post-pandemic inflation surge recedes further into the past, new price levels may become the accepted norm, reducing the psychological impact of “sticker shock.”

Conclusion: A Tale of Two Economies, One Nation

The Main Street vs. Wall Street divide is a powerful lens through which to view America’s complex economic and social landscape. It reveals that the economy is not a monolith but a collection of interconnected, yet often contradictory, systems.

Wall Street’s health is a necessary component of a functioning modern economy, fueling investment, innovation, and retirement savings. But it is not a sufficient measure of national well-being. A soaring S&P 500 cannot, by itself, pay the rent or put food on the table.

The ultimate challenge for policymakers, business leaders, and society as a whole is to recognize that long-term, sustainable prosperity requires both robust capital markets and a confident, financially secure citizenry. A nation where corporate profits soar while consumer sentiment languishes is an unstable one. True economic strength is found not in the dichotomy between Main Street and Wall Street, but in their alignment—when the success of the markets reflects and contributes to the broad-based prosperity of the people.

Decoding this sentiment divide is the first step toward building an economy that works for both.

Read more: Inflation Warfare: Is the Fed Winning the Battle Without Triggering a Recession?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: If the stock market is at an all-time high, doesn’t that mean the economy is great for everyone?

Not necessarily. The stock market reflects the anticipated future profits of large, publicly traded companies. It is influenced by global events, monetary policy, and investor sentiment. It is not a direct gauge of the day-to-day financial well-being of the average household, which is more concerned with the cost of living, wage growth, and local economic conditions. The two can, and often do, diverge.

Q2: I keep hearing that wages are rising. Why don’t I feel better off?

This is likely due to the difference between nominal wages (the dollar amount on your paycheck) and real wages (your purchasing power after inflation). While nominal wage growth has been strong, for much of the post-pandemic period, it lagged behind inflation. Even now, as real wage growth turns positive, many are still catching up from the cumulative inflation of the past few years. Furthermore, the costs of major expenses like housing and healthcare have risen dramatically, absorbing much of the wage gains.

Q3: What is the “vibecession”?

A term coined by Kyla Scanlon, the “vibecession” refers to the phenomenon where consumer sentiment about the economy is in recessionary territory (“the vibes are off”) even though hard economic data like GDP growth and employment remain strong. It highlights the growing gap between macroeconomic statistics and the public’s mood, driven by factors like inflation fatigue, political polarization, and social media narratives.

Q4: How does the Federal Reserve’s policy affect this divide?

The Fed’s primary tool is interest rates. Raising rates is intended to cool inflation by slowing the economy. This has a direct, negative impact on Main Street by making mortgages, car loans, and credit card debt more expensive. For Wall Street, the effect is more complex; higher rates can hurt stock valuations but are also a signal that the Fed is serious about taming inflation, which is good for long-term stability. The policy inherently creates tension between the two.

Q5: Who is right, Main Street or Wall Street?

This is the wrong question. Both are “right” from their own frames of reference. Wall Street is correctly observing strong corporate profits and a resilient economy. Main Street is correctly observing a high and stressful cost of living. The disconnect isn’t about who is right, but about understanding that the economy serves different functions for different actors. A complete picture requires acknowledging both perspectives.

Q6: Is this divide a new phenomenon?

No, a tension between Main Street and Wall Street has existed for over a century. However, the specific conditions of the post-pandemic era—unprecedented fiscal stimulus, supply chain shocks, a rapid spike in inflation, and a swift interest rate response—have amplified the divide to an unusual degree, making it a central feature of the current economic and political discourse.

Q7: As a small business owner, I feel caught in the middle. Why?

Small businesses are the literal intersection of Main Street and Wall Street. You experience the Main Street pressures directly: higher costs for inventory, supplies, and labor, and a customer base that may be pulling back due to inflation. At the same time, you may rely on lines of credit or loans, which have become more expensive due to Wall Street-influenced Fed policy. You are on the front lines of the divide, navigating the pressures from both sides.