For decades following the Cold War, a prevailing sense of linear progress dominated the Western financial mindset. The narrative, famously encapsulated by Francis Fukuyama as the “end of history,” suggested a global convergence towards liberal democracy and free-market capitalism. This era, characterized by hyper-globalization, just-in-time supply chains, and a general decline in interstate conflict, created a fertile ground for a specific breed of investment strategy. The primary goals were efficiency, cost minimization, and capitalizing on emerging market growth, with geopolitical risk often relegated to a peripheral concern—a “tail risk” to be managed, not a central driver of portfolio construction.

Today, that paradigm lies in ruins. The geopolitical landscape is experiencing violent tremors, from a major land war in Europe to strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific, persistent instability in the Middle East, and the weaponization of economic interdependence. For US investors, from large institutions to individual retirees, these conflicts are no longer distant headlines. They are fundamental forces actively reshaping the calculus of risk and return, compelling a profound and structural rethink of investment strategies for the 21st century.

This article will delve into the mechanisms through which these geopolitical tremors are transforming US investment approaches. We will explore the decline of globalization, the rise of security as an investment criterion, the shifting dynamics of the global monetary system, and the practical strategies investors are employing to navigate this new, more volatile world.

Part 1: The Great Unraveling – From Globalization to Fragmentation

The post-Cold War order was built on the bedrock of economic integration. The assumption was that deep trade links and mutual economic gain would deter major conflict. This belief fueled an unprecedented era of globalization.

1.1 The Efficiency Paradigm and Its Pitfalls

For corporations and investors, the mantra was “efficiency.” Supply chains were optimized for cost, leading to a massive reliance on single-source, low-cost manufacturing hubs, most notably China. This delivered decades of disinflation and high corporate profits, which in turn buoyed equity markets. Investment strategies heavily favored multinational corporations that could leverage this global arbitrage. The primary risks considered were cyclical: recessions, inflation, and central bank policy shifts. Geopolitics was a secondary variable.

1.2 The Shock of Interdependence Weaponization

The turning point was the realization that economic interdependence could be weaponized. The 2022 invasion of Ukraine was a watershed moment. The subsequent, sweeping sanctions imposed by the US and its allies—freezing central bank assets, restricting access to the SWIFT financial messaging system, and embargoing key commodities—demonstrated that the tools of the global financial infrastructure could be deployed as instruments of war.

This shattered a core tenet of the old system: the perceived sanctity of sovereign assets and the neutrality of financial networks. For investors, it introduced a new dimension of risk: sovereign policy risk. An asset’s value could now be dramatically altered not by its fundamentals, but by the geopolitical actions of its home country and the retaliatory policies of the US and its allies. Holding Russian equities or bonds in February 2022 was not a bet on corporate performance, but a bet on the state of NATO-Russia relations—a bet many lost catastrophically.

1.3 The Emergence of Bloc-Based Economics

The result is a rapid move towards a fragmented world, often described as “slowbalization” or “fragmentation.” The world is reorganizing into loose, competing economic blocs:

- The US-Led Bloc: Including G7 nations, NATO allies, and key partners like Australia and South Korea.

- The China-Russia Axis: Encompassing nations aligned through the BRICS+ framework and those seeking an alternative to the US-led order.

- The Non-Aligned Middle: A large group of countries, primarily in the Global South (e.g., India, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia), that are trading and engaging with both blocs, seeking to maximize their own advantage.

This fragmentation creates a “friend-shoring” or “near-shoring” imperative. Corporations and governments are now prioritizing supply chain security and resilience over pure cost efficiency. This represents a seismic shift in investment logic, moving from a model of global optimization to one of regional redundancy.

Part 2: The New Investment Playbook – Security, Resilience, and Real Assets

In response to this fragmented landscape, a new investment playbook is emerging. It moves beyond traditional financial metrics to incorporate geopolitical and national security criteria directly into the analysis.

2.1 The Reshoring and “Friendshoring” Boom

The vulnerabilities exposed by pandemic-era disruptions and the Ukraine war have catalyzed a massive reinvestment in domestic and allied-nation industrial capacity. US legislation like the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act are not merely domestic spending bills; they are geostrategic tools designed to reduce reliance on adversarial powers for critical goods like semiconductors and green energy components.

Investment Implications:

- Domestic Industrials & Manufacturing: Companies involved in factory construction, automation, and advanced machinery are poised for sustained growth. This includes industrial REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) focused on manufacturing sites and logistics hubs.

- Semiconductors: While chip designers like NVIDIA remain important, there is now a premium on companies involved in the physical fabrication of semiconductors, especially those building new fabs in the US, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan (e.g., Intel, TSMC, Samsung).

- Supply Chain Logistics: Firms that provide resilience through advanced logistics, inventory management software, and robotics are critical enablers of this transition.

2.2 The Return of the “War Economy” and Defense Spending

The war in Ukraine and rising tensions in the South China Sea have triggered the largest sustained increase in European and Asian defense budgets since the Cold War. For the first time in a generation, European nations are seriously committed to meeting NATO’s 2% of GDP defense spending target. Japan is undertaking its biggest military build-up in decades. This creates a multi-decade tailwind for the defense sector.

Investment Implications:

- Prime Defense Contractors: Companies like Lockheed Martin, RTX (formerly Raytheon), and Northrop Grumman, with their portfolios of long-cycle government contracts, offer visibility and resilience against economic downturns.

- Next-Generation Warfare: The nature of conflict is changing. This benefits companies in cybersecurity, drone technology, satellite communications (Starlink), and electronic warfare. Investing in a dedicated cybersecurity ETF, for instance, has become a modern-day hedge against geopolitical instability.

- Critical Munitions and Readiness: The war in Ukraine has highlighted stockpile shortages of conventional munitions. Companies that produce artillery shells, missiles, and other consumables of war are seeing surging demand.

2.3 The Commodity Super-Cycle and Real Assets

Geopolitical friction is inherently inflationary, particularly for commodities. Russia is a major supplier of oil, gas, and metals. The Middle East is central to global oil markets. Competition with China revolves heavily around access to critical minerals like cobalt, lithium, and rare earth elements. As globalization fractures, the free flow of these resources is impeded, creating supply shocks and sustained price pressures.

Investment Implications:

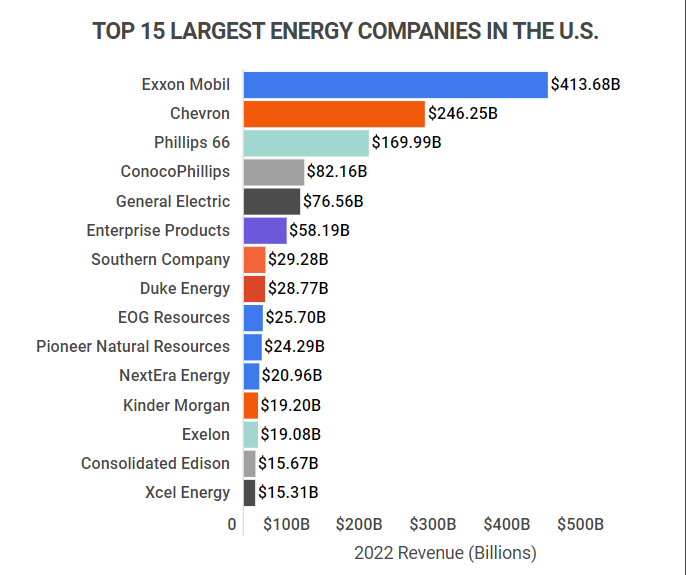

- Energy Security: The transition to renewables is a long-term strategic goal, but near-term energy security is paramount. This supports investment in traditional energy companies (Exxon, Chevron) with strong domestic or allied-nation production profiles. It also boosts the case for midstream infrastructure (pipelines, LNG export terminals) and nuclear power.

- Critical Minerals & Mining: Securing the supply chains for batteries, EVs, and defense hardware is a national priority. This directs capital towards mining companies operating in politically stable jurisdictions (e.g., Australia, Canada, the US) and those developing recycling and substitution technologies.

- Real Assets as a Hedge: In an environment of heightened inflation and geopolitical uncertainty, tangible “real assets” like commodities, infrastructure, and farmland regain their appeal as portfolio hedges. They hold intrinsic value that cannot be erased by sanctions or financial market volatility.

2.4 The Dilution of Dollar Dominance?

The use of financial sanctions has prompted a global search for alternatives to the US dollar-centric financial system. While the US dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency is not in immediate jeopardy, its monopoly is being challenged. Countries are increasingly exploring bilateral trade in local currencies, and central banks are diversifying their reserves away from dollars and euros.

Investment Implications:

- Gold’s Resurgence: Gold, the classic non-sovereign store of value, has seen renewed interest from central banks and investors alike as a hedge against both inflation and financial system risk.

- Currency Diversification: Sophisticated investors are increasingly looking at currency exposure not just as a source of return, but as a source of risk. Holding a portion of assets in currencies like the Swiss Franc or Singapore Dollar, or even in physical gold, can provide diversification from potential dollar volatility.

- Digital Assets’ Ambiguous Role: Cryptocurrencies have been touted as a potential haven from state control, but their volatility and regulatory uncertainty limit their current role as a reliable safe haven. However, the underlying blockchain technology for cross-border settlements is being explored by central banks themselves through Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs).

Read more: Beyond the Magnificent Seven: Is the S&P 500’s Rally Set to Broaden?

Part 3: Implementing the Strategy – A Practical Guide for Portfolios

Understanding the macro trends is one thing; implementing them in a portfolio is another. Here’s how the principles are being applied across different investor profiles.

3.1 For the Institutional Investor (Pensions, Endowments)

Institutions are undertaking a top-down overhaul of their strategic asset allocation.

- Geographic Tilting: Systematically reducing exposure to markets deemed to have high geopolitical risk (e.g., China, Russia) and increasing allocations to “safe” allied markets (e.g., North America, EU, Japan, India). This involves deep country-level due diligence beyond traditional economic metrics.

- Thematic Mandates: Allocating significant capital to dedicated thematic funds focused on “Supply Chain Resilience,” “National Security,” or “Energy Transition.”

- Direct Investments & Infrastructure: Moving beyond public markets to make direct investments in critical infrastructure, such as ports, data centers, and energy grids, which offer inflation-linked cash flows and strategic importance.

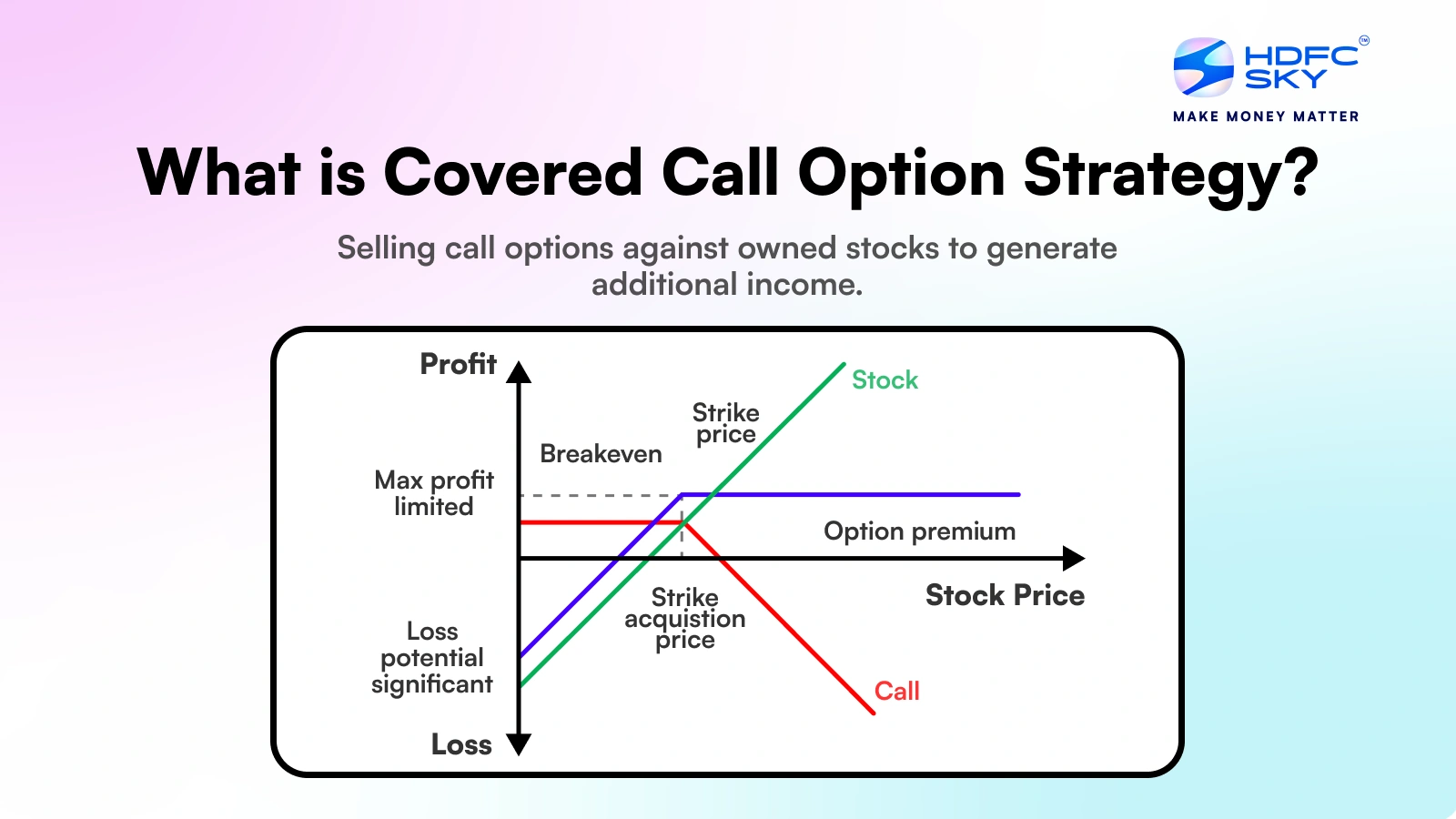

- Sophisticated Hedging: Using complex derivatives and strategies to hedge against specific geopolitical risks, such as a Taiwan Strait disruption or a spike in European natural gas prices.

3.2 For the Financial Advisor and Individual Investor

The core principles of diversification and long-term focus remain, but their application has evolved.

- Sector & Thematic ETF Selection: The easiest way to gain exposure to these trends is through Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs). Instead of just buying a broad S&P 500 fund, an investor might overlay a defense ETF (e.g., ITA), a cybersecurity ETF (e.g., CIBR), and a U.S. infrastructure ETF (e.g., PAVE).

- Enhanced Due Diligence: It is no longer enough to look at a company’s P/E ratio. Investors must ask: Where are its key suppliers and customers located? How exposed is it to politically unstable regions? Could its assets or operations be threatened by sanctions? A company’s ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) profile now critically includes the “G” for Governance and its geopolitical footprint.

- The New “Safe Havens”: The traditional 60/40 stock/bond portfolio is challenged. In this environment, “safe” assets may include:

- Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS): To hedge against the inflationary consequences of conflict and fragmentation.

- Domestic-Focused Equities: Companies that generate most of their revenue within the stable North American bloc.

- Gold and Commodities: As a non-correlated asset class and store of value.

- Avoiding Value Traps: Some emerging markets may appear cheap on traditional metrics, but they may be cheap for a reason—namely, high and unquantifiable geopolitical risk. The potential for high returns must be weighed against the risk of a total capital loss due to political events.

Conclusion: Navigating the New World Disorder

The age of geopolitical tranquility that enabled the investment strategies of the late 20th and early 21st centuries is over. We have entered a period of persistent systemic competition, where economic and security concerns are inextricably linked. For US investors, this is not a temporary condition to wait out; it is the new normal.

The successful investor of the future will be the one who recognizes that geopolitical analysis is no longer an exotic specialty but a core component of fundamental research. The strategies that will prevail are those built not just on the pursuit of efficiency, but on the pillars of resilience, security, and strategic alignment.

This requires a more active, more discerning, and arguably more cautious approach to capital allocation. The tremors reshaping our world are creating profound risks, but also defining new opportunities—in the industries that rebuild our industrial base, the technologies that secure our digital and physical frontiers, and the real assets that underpin a less stable global order. The task for investors is to build portfolios that can not only withstand the shocks but also thrive in the landscape they leave behind.

Read more: The Fed’s Tightrope: Can the US Economy Stick a Soft Landing in 2025?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Isn’t this just a temporary phase? Won’t things eventually return to normal?

While specific conflicts may de-escalate, the underlying structural shift is profound. The weaponization of economic interdependence has broken a fundamental trust. Both the US and China, for example, are now explicitly planning for decades of strategic competition. The drive for supply chain resilience and national security investment is embedded in long-term government policy and corporate boardroom strategy. A return to the hyper-globalized, geopolitically naive world of the 1990s is highly unlikely.

Q2: How much of my portfolio should I shift towards these “geopolitical” themes?

There is no one-size-fits-all answer, as it depends on your risk tolerance, time horizon, and existing portfolio. For most individual investors, a radical overallocation is not advisable. A more prudent approach is to use these themes as a tilt or an overlay to a well-diversified core portfolio. Allocating 10-20% of the equity portion of a portfolio to a combination of defense, cybersecurity, domestic industrial, and infrastructure ETFs could be a starting point for capturing these trends without taking on excessive concentration risk.

Q3: I’m invested in a broad, low-cost S&P 500 index fund. Is that no longer a good strategy?

The S&P 500 remains a cornerstone of US investing, and it is not obsolete. However, it is important to understand its new biases. The index is heavily weighted towards mega-cap technology companies, many of which have significant global exposure and supply chain dependencies, particularly in Asia. The S&P 500 strategy should now be viewed as the core, but investors may benefit from complementing it with more targeted investments that hedge its specific geopolitical vulnerabilities (e.g., adding a domestic-focused small-cap fund or a defense sector ETF).

Q4: What are the biggest risks of overreacting to geopolitical news?

The primary risk is making emotional, short-term trades based on headlines. Geopolitics moves in cycles that are often disconnected from market cycles. Selling all your international holdings after a negative news event often means locking in losses and missing the subsequent rebound. The goal is not to time the markets based on daily news, but to make a strategic, long-term asset allocation shift that acknowledges the new, higher level of systemic risk in certain regions and sectors.

Q5: How does this affect my bond holdings?

Significantly. Geopolitical risk creates two opposing forces for bonds. On one hand, bonds can still act as a “flight-to-safety” asset during a sudden crisis, causing prices to rise and yields to fall. On the other hand, the persistent inflationary pressures from deglobalization and defense spending can lead to higher long-term interest rates, which hurts bond prices. This is why TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) and shorter-duration bonds (which are less sensitive to interest rate changes) have become more attractive components of a fixed-income portfolio.

Q6: Is it time to pull all my money out of China and other emerging markets?

A blanket withdrawal is not necessarily the most sophisticated approach. The key is differentiation. The risk profile of China, a peer competitor to the US, is fundamentally different from that of a non-aligned emerging market like India or Brazil, which may actually benefit from being courted by both blocs. A more nuanced strategy involves:

- Drastically reducing or eliminating direct exposure to state-owned enterprises and companies in strategic sectors in adversarial nations.

- Being highly selective with private companies in those markets, focusing on those with strong governance and domestic-facing revenue streams.

- Increasing exposure to emerging markets in politically aligned or neutral countries that stand to benefit from supply chain diversification.